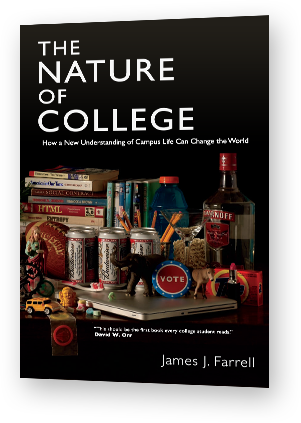

Toying with Materialism

Recently, I’m reading Life at Home in the 21st Century, a thorough ethno-archaeological dig through 27 American homes in the Los Angeles area. More later, but one sentence caught my eye: “While American children constitute a tiny fraction of the world’s population of children, U.S buyers are responsible for annually purchasing a mind-boggling 40 percent of the world’s toys.” It seems that we Americans love our children, and that we love them by teaching the lessons of materialism.

And what might kids learn from all the toys they have? I’m not sure, but here are a few suggestions from a kid’s perspective:

1) Fun is the primary purpose of life. Parents do buy educational toys, but not many, and nobody seriously thinks children will play with them very much.

2) Our own imaginations are inadequate to the task of having fun. If we’re going to play, we need toys, and we need instructions. Age-appropriate toys—as marked on the box—guide us through the process of maturation.

3) Plastic is the primary material of the cosmos. Later, of course, we discover that plastic toys are a life-cycle thing, but the primacy of plastic is learned early, along with the forgetfulness of its environmental impacts.

4) It’s important to have desires. The ads on TV tell us that, but so do the “wish lists” compiled for birthdays and Christmas and other holidays. At any given moment, a normal American wants something s/he doesn’t yet have.

5) It’s not enough to watch a movie or TV—you need to have the associated hardware that comes with happy meals or trips to Toys R Us.

6) There’s no such thing as enough. You may have 22 Barbies, but there’s always one more—or at least a new outfit. In this way, children are acculturated to the excesses of American life.

7) If Jimmy Jones has a toy, then I should have it to. I don’t know the concept yet, but I do know how to keep up with the Joneses.

8) Emotions can be expressed with stuff. Parental love manifests itself not just in care and feeding, but in dolls and action figures, Beanie babies and other plush toys, Matchbox cars and other automotive vehicles, board games and video games, as well as the pre-school plastic that shakes, babbles, rattles and rolls.

9) Toys are the payoff both for trauma and for good behavior. When Mom and Dad are out of town, when your feelings have been hurt, when you’ve done well in school, or when you need to be pacified, a toy is an appropriate response. This accustoms kids to a culture full of extrinsic rewards, and a closet full of forgotten trinkets and toys.

10) Toys are a way for parents to have time to themselves. When children have enough toys—or too many—parents expect us to occupy ourselves instead of occupying increasingly scarce adult time. Toys and games—especially video games—are often a way of telling children to keep our distance.

All toys, therefore, are educational toys, and they teach us how to live in a consumer society, but not how to create a satisfying and sustainable society that might last more than a lifetime.

About the Author

About the Author